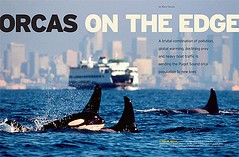

A brutal combination of pollution, global warming, declining prey and heavy boat traffic is sending the Puget Sound orca population to new lows

NATIONAL WILDLIFE MAGAZINE

Oct/Nov 2006, vol. 44 no. 6

Orcas on the Edge

By Ken Olsen

A brutal combination of pollution, global warming, declining prey and heavy boat traffic is sending the Puget Sound orca population to new lows

SEEING KILLER WHALES ply the waters of Washington State’s Puget Sound has long been a great thrill for Seattle-area residents. No other U.S. urban community can boast of resident orcas a few miles from downtown. Whale watching there is a multi-million-dollar tourist draw. As one orca expert puts it, “Everybody wants a kiss from a killer whale.”

But the thrill may soon be gone.

Three orca pods living in Puget Sound from May through October, known as the southern resident killer whale population, were declared federally endangered late last year by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the federal agency responsible for protecting marine species. Scientists believe the decline of wild chinook salmon—a major orca food source—as well as global warming, toxic pollution and vessel noise could eliminate this orca population, which ranges beyond Puget Sound into the San Juan Islands and Georgia Strait. “They are teetering,” says Ken Balcomb, senior scientist at the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, Washington. It is “highly likely,” Balcomb adds, that this population of killer whales will be extinct within 100 years if conditions do not improve for both whales and salmon.

“The Puget Sound is our backyard,” adds James Schroeder, an NWF senior environmental policy specialist. “If it’s unhealthy for killer whales because the water is polluted, the sediments are laced with toxins and the food web has collapsed, it’s ultimately uninhabitable for humans.”

The largest members of the dolphin family, orcas weigh about 400 pounds at birth. Adults can measure more than 25 feet long, weigh more than 8 tons and sport a 6-foot dorsal fin. Females can live into their eighties.

Orcas are found in every ocean and, next to humans, are the most widely distributed mammal in the world. Two distinct types of killer whales travel the seas—transients and residents—which are distinguished by differences in genetics, language and food preference. They do not interbreed or even mingle. Transients live in small pods of three to seven and often travel far out to sea, subsisting on marine mammals such as seals, sea lions, dolphins and whales. Residents live closer to shore in pods of 10 to 20, are known for their jumping and splashing and eat only fish, which they sometimes stun with tail slaps. Transients rarely jump or splash and even use sonar less often, behaviors probably designed to avoid alerting the marine mammals they hunt.

Individual orcas can be identified by distinct gray swaths on their backs and flanks near their dorsal fins, called saddle patches. Using these patches, biologists have named each of Puget Sound’s approximately 87 killer whales, which are part of a population that has been carefully studied since 1970, making them some of the best-known orcas in the world. All indications are that the southern resident population and the nearby British Columbia, or northern, resident orcas live primarily on chinook salmon, which are preferred probably because they are the largest salmon, have the highest fat content and are available year-round.

When West Coast wild chinook stocks plummeted in the mid-1990s, the southern resident orca population dropped from 99 in 1995 to about 80 in 2001. The northern resident population went from 219 to 202 during roughly the same time period. “Mortality in some years was 300 percent greater than we expected,” says John K.B. Ford of Fisheries and Oceans Canada—Canada’s lead federal manager of oceans and inland waters—who has studied killer whales for 30 years.

West Coast waters once were rich with wild salmon. The Columbia and Snake Rivers alone produced between 10 million and 16 million salmon yearly, the majority of them chinook. Overfishing in the late 1800s and early 1900s, followed by decades of dam building, logging and other salmon-habitat destruction have reduced wild salmon to a fraction of their original abundance. Today, Columbia and Snake River wild fish runs number only in the tens of thousands. “Perhaps the single greatest change in food availability for resident killer whales since the late 1800s has been the decline of salmon in the Columbia River basin,” according to the NMFS draft orca recovery plan. Even British Columbia’s resident killer whales, declared threatened by Canada in 2001, feed on Columbia and Snake River salmon. “In order to save our orcas, we need to save the salmon runs that sustain them,” Schroeder says.

Beleaguered salmon populations are now further jeopardized by a new challenge, global warming, which is heating some rivers and streams to temperatures lethal to fish. The average temperature of British Columbia’s Fraser River, for example, increased about 1.8 degrees F from 1953 to 1998, yielding a 50-percent mortality rate among the river’s sockeye salmon. “The higher river temperatures are largely due to global warming, as opposed to dams and other significant human-caused problems,” says Patty Glick, an NWF global warming specialist. The Canadian Ministry of Environment agrees. Citing the fact that the climate is warming, the ministry declared in a 2002 report that logging, agriculture and industrial factors have small impact on river temperature “in comparison to the impact of climate change.”

Warming oceans pose another problem—they produce less food for salmon and other fish. Oceans also absorb carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas produced by burning coal and other fossil fuels. This absorption changes the acidity of seawater, which could have catastrophic consequences for marine life. In addition, global warming is expected to alter the timing and amount of precipitation that keeps water flowing in the rivers and streams where salmon spawn. As rain and snowfall patterns change, chinook runs that now occur throughout the year could be confined to just a few of the wetter months—leaving Puget Sound orcas without salmon for long periods of time.

Salmon scarcity actually hits orcas with a one-two punch. The decline in food is a problem on the one hand, while the toxicity of the fish is a problem on the other. Puget Sound is steeped in toxics from pulp and paper mills, oil refineries, ports, boatyards and storm-water runoff. Salmon and other fish store in their bodies toxic pollutants they absorb from this environment. As a result of eating these contaminated fish, Puget Sound killer whales have some of the highest concentrations of highly carcinogenic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) of any marine mammal in the world, says Gary Wiles, a wildlife biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. They also have high levels of polybrominated diphenyl ethers, which are toxic fire retardants.

As salmon numbers dwindle, killer whales burn blubber to survive, transferring toxics from blubber to vital organs. “When orcas metabolize fat that’s 1,000 parts per million PCBs, it’s phenomenally toxic,” Balcomb says. “Even trace amounts of PCBs disrupt the orcas’ endocrine systems, adversely affecting reproduction and their immune systems. We have seen whales become emaciated and disappear. And lots of reproduction-age females are not reproducing.”

Noise from the thousands of aquatic vessels cruising orca range may compound the food scarcity problem. Puget Sound is teeming with ferries, naval flotillas, whale-watching boats and other noisy craft that interfere with sonar, the clicking sounds orcas use like radar to find salmon. “There’s probably a lot of synergistic interactions between these stressors,” Ford says. “When there are fewer salmon, the whales have to work harder to find food. More noise may make it harder to find those fewer fish. The increased nutritional stress may lead to immuno-suppression and make the orcas more susceptible to disease.”

Saving Puget Sound orcas will require cleaning up toxic waste sites, stemming storm-water pollution and stopping global warming. The most critical step, however, is restoring salmon runs so orcas have enough to eat. “The Snake River basin once produced more than a third of all the chinook in the Columbia River basin,” Schroeder says. “If the federal government would take out the four outdated lower Snake River dams, it would go a long way toward recovering endangered Columbia River salmon and Puget Sound killer whales.”

A measure the government actually is taking also is likely to help the orcas. NMFS in June proposed new restrictions on development in about 2,500 square miles of inland waters, from Olympia, Washington, north to the Canadian border. The proposal, which covers almost all of Puget Sound, could be final as early as November, requiring any projects using federal funds or conducted under federal permits to include orca protections.

In the end, orca conservation is about a lot more than saving the Puget Sound’s magnificent killer whales. “We ignore this looming environmental problem at our own peril,” Balcomb says. “The orcas are the ultimate indicator of the health of the marine ecosystem. And that ecosystem is two-thirds of our planet.”

Washington journalist Ken Olsen wrote about farmers restoring sage grouse habitat in the April/May issue.

No comments:

Post a Comment